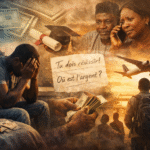

The systematic discrimination against the Bamiléké people of Cameroon represents one of the most persistent and documented cases of ethnic persecution in post-colonial Africa. Far from being a recent phenomenon, anti-Bamiléké sentiment—termed « Bamiphobia »—has deep colonial roots and has evolved into a sophisticated tool of political control that threatens Cameroon’s democratic foundations and social cohesion.

Colonial Genesis: The « Pebble in the Shoe »

The origins of institutionalized Bamiphobia can be traced to colonial anxieties about Bamiléké economic dynamism and political resistance. In March 1960, French colonial officer Jean-Marie Lamberton crystallized this sentiment in his article « Les Bamiléké dans le Cameroun d’aujourd’hui » (The Bamiléké in Today’s Cameroon), writing: « Cameroon embarks on the path to independence with a very troublesome pebble in its shoe. This pebble is the presence of an ethnic minority: The Bamiléké. »

This colonial framing established the Bamiléké—comprising approximately 25% of Cameroon’s population—as an existential threat to national stability. The metaphor of the « pebble » would prove prophetic, as successive post-independence governments have maintained this narrative to justify systematic exclusion and violence.

A Chronicle of Violence: From Independence to Present

Early Post-Independence Massacres

The transition to independence was marked by targeted violence against Bamiléké communities. The April 24, 1960, fire in Douala’s Congo neighborhood destroyed over 1,000 wooden houses and killed between 19 and 3,000 people, depending on sources. This incident, widely believed to be arson, demonstrated the willingness to use mass violence against Bamiléké populations.

The systematic nature of this persecution became even clearer with the December 31, 1966, Tombel massacres, where local militias conducted methodical extermination campaigns against Bamiléké villages, officially killing 236 people and wounding over 1,000.

Institutional Discrimination

Beyond physical violence, Bamiphobia has manifested through institutional discrimination. A telling example occurred in 1987, when 51 of 80 « indigenous » priests in Douala’s archdiocese sent a memorandum to the Vatican, denouncing the « Bamilékization » of the Church hierarchy following the appointment of Gabriel Simo as auxiliary bishop. This incident revealed how deeply anti-Bamiléké sentiment had penetrated even religious institutions.

In July 2012, while serving as Archbishop of Yaoundé and Grand Chancellor of the Catholic University of Central Africa (UCAC), Mgr Tonye Bakot addressed a letter to Father Martin Birba, Dean of the Faculty of Social Sciences and Management.

The subject of the letter, “Statistics”, had nothing to do with academic instruction. Instead, Mgr Tonye Bakot raised concerns bordering on ethnic profiling.

Key Points from the Letter

- 48% of associate lecturers came from the West Province of Cameroon.

- 31.5% of permanent lecturers were also from the West Province.

- Over 60% of the students enrolled in the faculty originated from the same region.

For Mgr Tonye Bakot, these figures revealed a “problem” that, in his view, required corrective measures, potentially involving positive or negative discrimination depending on one’s perspective.

The Archbishop also referenced existing practices such as anonymous grading corrections and even relayed unsubstantiated rumors alleging that some students from the West used “secret signals” to communicate with lecturers from their region during competitive exams.

It is worth noting that admission into this institution is highly competitive, making these remarks particularly sensitive in the academic context.

On July 17, 1999, Monsignor André Wouking was appointed Archbishop of Yaoundé, replacing Monsignor Jean Zoa, who had passed away a few months earlier.

On the day of his enthronement, individuals claiming to belong to the Béti community set up barricades on the Bafoussam–Yaoundé national road with the intention of preventing Bamiléké people from entering the capital.

One could read graffiti written on the road at the site of the protests:

“No Bamiléké Archbishop in Yaoundé.”

According to an edition of the French Catholic newspaper La Croix, it reported:

“To the cries of ‘We refuse a Bamiléké Archbishop’ and ‘The Bamilékés want everything, but they will not have this archdiocese’, a few hundred Cameroonians protested at the entrances and exits of the capital Yaoundé on Sunday.”

Political Weaponization in the Democratic Era

The return to multiparty politics in the 1990s intensified rather than diminished ethnic tensions. During the 1991 political upheaval, Sawa elites demanded that Bamiléké merchants and property owners « return stolen lands. » This rhetoric culminated in October 1992 violence in Ebolowa, where local militias burned and looted Grassfields residents’ homes and businesses in post-electoral violence.

Contemporary Manifestations: Digital Age Hatred

Media and Political Discourse

Modern Bamiphobia has adapted to contemporary media landscapes. Television discussions regularly feature coded language targeting Bamiléké political participation, while social media platforms have become venues for explicit ethnic hatred. The case of Professor Maurice Kamto’s presidential candidacy exemplifies this pattern—while northern candidates like Bello Bouba and Issa Tchiroma receive regional support without criticism, Kamto faced accusations of tribalism and separatism.

Institutional Discrimination Continues

Recent incidents demonstrate the persistence of institutional bias. In December 2024, Deputy Mathurin Germain Bindoua wrote to President Paul Biya’s office criticizing the « majority of Bamiléké-origin managers » at ENEO, the national electricity company. Such complaints reveal how professional competence is reframed as an ethnic conspiracy when achieved by Bamiléké citizens.

Escalating Rhetoric

Perhaps most alarmingly, digital platforms have enabled increasingly violent discourse. In February 2025, during a TikTok live session with over 270 viewers, a participant living in Europe explicitly called for genocide against Bamiléké populations, declaring: « For Cameroon to develop, there must be a genocide in Cameroon… all these Bamiléké must be killed. » Another continued, « Because we’re fed up with those people. Here’s a people to whom the government has given everything, and they still want more.

With this whole Kamto thing to replace Biya, me myself, I’ll go down to Cameroon and pick up a machete! »

The Actors of Hatred

State and Para-State Actors

The Cameroonian state has alternated between tolerating and actively promoting anti-Bamiléké sentiment. While rarely engaging in explicit hate speech, state institutions consistently exclude Bamiléké voices from key decision-making positions, creating what scholar Achille Mbembe calls a « technology of power. »

Political Elites

Opposition and ruling party figures alike have weaponized ethnic divisions. The pattern is consistent: when Bamiléké candidates emerge, they face questions about ethnic loyalty that other candidates avoid. This double standard has become so normalized that it passes without comment in mainstream political discourse.

Civil Society and Religious Institutions

Religious and civil society organizations have sometimes amplified rather than countered ethnic prejudices. The Catholic Church’s internal memo about « Bamilékization » demonstrates how supposedly neutral institutions can become vehicles for ethnic discrimination.

Digital Influencers and Diaspora Voices

Social media has democratized hate speech, allowing individuals with large followings to promote ethnic divisions. The February 2025 genocide incitement on TikTok represents an extreme but logical endpoint of years of unchecked online hatred.

Systemic Impact

Economic Consequences

Despite—or perhaps because of—their economic success, Bamiléké communities face systematic barriers. Their achievements in commerce and education are reframed as evidence of ethnic conspiracy rather than individual merit or community values of entrepreneurship and education.

Political Exclusion

No Bamiléké has ever served as Cameroon’s president, despite their demographic weight and political participation. This exclusion is maintained through both formal barriers (such as residency requirements that effectively eliminate diaspora candidates) and informal pressure that labels Bamiléké political ambition as tribal supremacism.

Social Fragmentation

Bamiphobia has contributed to broader social fragmentation, as ethnic suspicion replaces national solidarity. Children learn ethnic stereotypes in school playgrounds, while adults navigate professional and social relationships through ethnic calculations.

The Path Forward: Breaking the Cycle

Truth and Reconciliation

Addressing Bamiphobia requires confronting uncomfortable historical truths. The violence of the independence era, the systematic exclusion of subsequent decades, and the normalization of ethnic hatred all demand acknowledgment before genuine reconciliation becomes possible.

Institutional Reform

Democratic institutions must actively counter rather than enable ethnic discrimination. This includes media regulation to prevent hate speech, electoral reforms to ensure fair participation, and judicial independence to protect minority rights.

Cultural Transformation

Perhaps most importantly, Cameroon needs a fundamental shift in national discourse—from viewing diversity as a threat to embracing it as a strength. This requires leadership across all sectors willing to model inclusive behavior and challenge ethnic stereotyping.

The persistence of anti-Bamiléké hatred represents a profound failure of Cameroon’s post-colonial project. Until this « pebble » is removed from the nation’s shoe—not by crushing it, but by understanding and addressing the conditions that created it—Cameroon will continue limping toward a democratic future that remains frustratingly out of reach.

2 Comments

[…] more than 20 percent of Cameroon and dominates commercial trading but has long been subject to political exclusion and hate speech; anti-Bamileke rhetoric has grown since Kamto was targeted by the […]

[…] more than 20 percent of Cameroon and dominates commercial trading but has long been subject to political exclusion and hate speech; anti-Bamileke rhetoric has grown since Kamto was targeted by the […]