By Voix-Plurielles

On the morning of September 12, 1959, a young man named Fossi Jacob was led to the edge of the Métché Falls in western Cameroon. He was not alone—many other prisoners of conscience had already been executed in this place of terror, their bodies cast into the roaring waters below. What happened next would etch Fossi’s name forever into the collective memory of the Bamiléké people and into the broader narrative of Cameroon’s silenced history.

A Life Shaped by Resistance

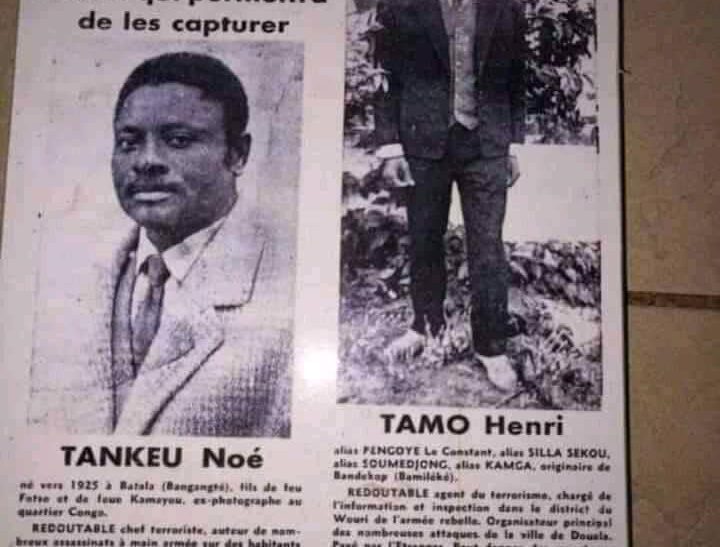

Fossi Jacob was part of a generation of Bamiléké men and women who came of age during the struggle for independence in Cameroon. The 1950s were a decade of both hope and brutal repression. The Union des Populations du Cameroun (UPC), the nationalist party demanding self-determination, was outlawed by French authorities, and its members hunted down. In the West, the Bamiléké homeland became the epicenter of what survivors now call the Bamiléké genocide (1955–1971), a campaign of extermination designed to crush resistance. Fossi, a UPC militant, embraced the cause of liberation. For him, independence was not just about political sovereignty—it was about dignity, justice, and the right of his people to live free of fear.

The Tragedy at Métché Falls

The circumstances of his death remain one of the most haunting episodes of that period. Captured by colonial forces, Fossi was taken to the Métché Falls, a site used systematically for mass executions. Prisoners were thrown into the waters, their deaths meant to erase both their lives and the ideals they carried. But Fossi’s final act ensured that he could not be forgotten. According to oral accounts, he requested to speak to a French official, offering supposed information about fellow “rebels.” As the official leaned in, Fossi seized him and leapt, dragging his executioner with him into the rushing waters below. Both died instantly. It was an act at once desperate and defiant—a refusal to die passively, a final gesture of resistance.

Symbol of a Silenced Genocide

For decades, the story of Fossi Jacob lived primarily in whispers. Official histories in Cameroon erased or minimized the Bamiléké genocide, branding men like Fossi as “bandits” or “rebels.” Yet within Bamiléké communities—both at home and across the diaspora—his name was invoked as that of a martyr. He became a symbol not only of the brutality of colonial repression but also of the indomitable will to resist. His death at Métché Falls transformed that site into sacred ground, a place where memory and mourning converge. Today, it is visited not only as a natural wonder but also as a memorial to lives stolen and voices silenced. Fossi’s story is inseparable from this geography of pain and remembrance.

Legacy in the Diaspora and Memory Work

In recent years, the Bamiléké diaspora has played a crucial role in reclaiming figures like Fossi Jacob for history. Through cultural associations, commemorations, and research initiatives, they have insisted that the genocide be recognized as part of Cameroon’s national narrative and as part of global conversations about colonial violence. Fossi’s story features prominently in these efforts. For activists, he embodies the courage of a generation betrayed by both colonial and postcolonial regimes. For educators, he represents the urgency of teaching suppressed histories. For the diaspora, he is a bridge between the homeland and their work of remembrance abroad.

Conclusion: A Name That Must Be Spoken

To honor Fossi Jacob is to honor all the unnamed who perished during the Bamiléké genocide. His life and death remind us that history is not abstract—it is carried in the bodies, voices, and silences of individuals. By reclaiming his story, the Bamiléké affirm that memory is resistance and that justice begins with truth. Today, as commemorations grow stronger and younger generations take up the mantle of remembrance, Fossi Jacob’s place in history is assured. He is no longer a silenced prisoner cast into the river of oblivion. He is a martyr, a symbol, and a guardian of collective memory—his story echoing like the roar of the Métché Falls, impossible to silence.

Timeline of the Bamiléké Genocide

- 1955 – The Union des Populations du Cameroun (UPC) is banned by French colonial authorities. Repression intensifies.

- 1957–1958 – Bamiléké resistance in the Western region grows. Villages are burned, populations displaced.

- 1959 – Executions at Métché Falls and other sites. Figures like Fossi Jacob are killed as part of mass purges.

- 1960 – Cameroon gains independence, but violence continues under the new regime with French support.

- 1961–1971 – Systematic campaigns target Bamiléké populations: assassinations, mass killings, torture, forced relocation.

- 1971 – Official repression of UPC and Bamiléké resistance was largely suppressed. Memory work begins underground, sustained through oral tradition and diaspora activism.

Why Métché Falls Matters

The Métché Falls, near Bafoussam in western Cameroon, is a place of breathtaking natural beauty—and harrowing memory. During the height of repression in the late 1950s, colonial and loyalist forces used the site as an execution ground, pushing political prisoners and suspected nationalists into the falls to their deaths. For the Bamiléké, Métché Falls is more than a tourist attraction. It is sacred ground, a site of martyrdom where lives like Fossi Jacob’s were violently ended. Today, it serves as both a memorial and a symbol: a reminder of loss, resilience, and the unbroken thread of memory that binds generations.